The story of a home recording that became an album, as told by Bruce's long-time engineer Toby Scott

By Daniel Keller  In the early days of the home recording revolution, it was an oft-cited fact that the Beatles' legendary Sgt. Pepper was recorded on a four track; this to inspire us to make the most of our semi-pro gear. But let's be clear - the four-tracks at Abbey Road were professional-grade machines, linked together and run by some of the world's brightest, most innovative engineers, at one of the world's most technically advanced studios. This was hardly the stuff of the personal studio revolution.

In the early days of the home recording revolution, it was an oft-cited fact that the Beatles' legendary Sgt. Pepper was recorded on a four track; this to inspire us to make the most of our semi-pro gear. But let's be clear - the four-tracks at Abbey Road were professional-grade machines, linked together and run by some of the world's brightest, most innovative engineers, at one of the world's most technically advanced studios. This was hardly the stuff of the personal studio revolution.

A far more appropriate example of overcoming technical limitations might be the story of Bruce Springsteen's critically acclaimed dark horse epic, Nebraska. Although most people know the album was recorded on a Tascam PortaStudio with a pair of Shure SM57's, few are aware of the almost impossible circumstances under which the album was born. Here's the story as told by Toby Scott, Bruce's long-time recording/mix engineer.

"I'd gotten involved with Bruce in 1980, mixing The River, and subsequent to that he asked me to mix some live shows for him" recalls Scott. "Around 1982 he was producing an album with Steve Van Zandt for Gary US Bonds, and he called me in to mix that record. Soon afterward, Bruce decided he wanted to move the process to New York and commence work on what would become Born in the USA.

"At the beginning of the project Bruce came into the studio with a cassette and said, 'I've got a bunch of song demos here.' He said some were rock songs he wanted to cut with the band, but others were quieter tunes that might not be appropriate for the whole band. (In fact, it turned out some of the songs really didn't fit with the album overall, and they eventually decided those should end up on a different record.)

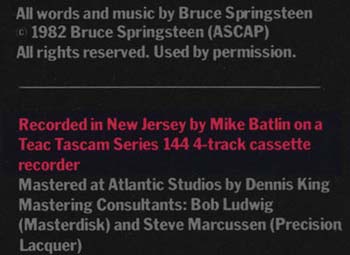

"Now, in those days it wasn't so common for an artist to have tunes demoed before going into the studio, and I asked Bruce where he'd put those demos together. It seems that around January of '82, he'd enlisted his guitar roadie, Mike Batlan, telling him 'go find me a little tape machine - nothing too sophisticated, just something I can do overdubs on.' So Mike walks into a local music store and the clerk sells him a Teac (Tascam) 144, which had been out for a year or two. It was a simple, straight-ahead machine - perfect for what Bruce wanted to do.  "Mike bought the PortaStudio, a pair of SM57's and a pair of mic stands. Bruce was living in a house in Long Branch, NJ, and he told Mike to set it all up in the spare bedroom. Well, Mike was a guitar roadie, not all that technical himself, and he didn't have much of a chance to get familiar with the gear before Bruce wanted to record. He got some levels and tried to make sure the meters didn't go into the red too much, and he may have listened briefly with headphones, but Bruce was eager to get going, so I don't think he got much beyond the basics. In fact, on some of the first songs they recorded, you can hear a bit of distortion where Mike is still getting his levels.

"Mike bought the PortaStudio, a pair of SM57's and a pair of mic stands. Bruce was living in a house in Long Branch, NJ, and he told Mike to set it all up in the spare bedroom. Well, Mike was a guitar roadie, not all that technical himself, and he didn't have much of a chance to get familiar with the gear before Bruce wanted to record. He got some levels and tried to make sure the meters didn't go into the red too much, and he may have listened briefly with headphones, but Bruce was eager to get going, so I don't think he got much beyond the basics. In fact, on some of the first songs they recorded, you can hear a bit of distortion where Mike is still getting his levels.

"The recording of Born in the USA went a lot quicker than Bruce had expected. The band had been touring together for several years and was very tight, even after several months off, so the tracks came together quickly. As for me, I'd been an L.A. session engineer and was used to getting things done quickly, so the mixes also went fast. Bruce had been accustomed to taking months on a record, so he was a bit surprised - here we were in the third or fourth week and we were already mixing. At that point, he decided we should start working on some of the other, more acoustic songs.

"So we approached those songs as a whole different batch of demos. He figured we might have Max play some light percussion on some songs, or maybe a synth pad from Roy, but these were songs that wouldn't really fit with the sound of the whole E-Street Band. We tried several different takes over a few days' time, but Bruce would always say it didn't sound quite right. He kept pulling out that cassette and saying 'I want it to sound more like this.'

"Over the course of our recording, I started to find out a few other interesting details about how they'd recorded these tunes. It turns out they'd mixed everything through an old Gibson Echoplex - the ones with an endless tape loop for slapback - and that machine had since gone to meet its maker.

"It seems also that during the recording process, Mike had never really figured out what that little round knob next to the transport controls was for, and had left it at around the two o'clock position. So they'd ended up recording everything with the varispeed set fast. Then he thought well, maybe it shouldn't be in that position, so he turned it back to twelve o'clock for mixdown.

"Then there was the mixdown deck. Turns out they mixed down to the only other deck they had around that had a line input, which was an old Panasonic boom box with a history of its own. You see, Bruce had a canoe he liked to take out on this little branch of the river that flowed near his house, and the previous summer during one of those trips the boom box had fallen overboard and sunk in the mud. Later that day when the tide went out, he retrieved it, brought it back to the house, hosed off the mud and left it on the porch for dead. About a week later, he was sitting on the porch reading the Sunday paper, and the boom box all of a sudden comes back to life.

"So now it's the following January, and forgetting about all that, this was the machine they used for their mixdown deck. I should add that neither Bruce nor Mike were all that familiar with the concept of head cleaning or alignment, so the heads on the boom box, the PortaStudio and the Echoplex never did get a cleaning.

"Now, from January when they mixed those demos through around April, Bruce had walked around with the only copy of these mixes in the front pocket of his jeans jacket the whole time. And here was the tape he was holding up in the studio and saying, 'there's just something about the atmosphere on this tape. Can't we just master off this?'

"Well of course you could just about hear the moans coming from all the engineers in the room. We were all trained to get the best sound possible on the best equipment, and here was our artist asking us to go against pretty much everything we knew. And I said 'yes Bruce, we could. I'm not sure you'll like it, but we could.' I could've said no, that the sound wasn't good enough to master off of, but that's not what it's all about. We work for the artist, and we're there to help them achieve their vision, even if it goes against all the rules of engineering. I guess that's probably part of why I'm still working for Bruce after all these years.

"So I gave that cassette to an assistant and told him to copy it onto a good piece of tape. Then we went around to four or five different mastering facilities, but no one could get it onto a lacquer - there was so much phasing and other odd sonic characteristics, the needle kept jumping out of the grooves. We went to Bob Ludwig, Steve Marcussen at Precision, Sterling Sound, CBS. Finally we ended up at Atlantic in New York, and Dennis King tried one time and also couldn't get it onto disk. So we had him try a different technique, putting it onto disk at a much lower level, and that seemed to work. In the end we ended up having Bob Ludwig use his EQ and his mastering facility, but with Dennis' mastering parameters. And that's the master we ended up using.

"The album sounds the way it does because of all those factors - the multiple tapes, the dirty heads, the varispeed - it's all part of the overall atmosphere, and part of what Bruce liked about the songs. At the end of the day, he was able to get his ideas down on tape, in his own environment, thanks to a PortaStudio and a pair of 57's, and that was the equipment he needed to get the sound he was looking for."

Two decades later, the home studio landscape has evolved dramatically, and it seems almost impossible to imagine any musician, let alone someone of Bruce Springsteen's stature, recording demos under such primitive conditions. But even as we've moved from PortaStudios and 57's to computer recording and digital DSP, one thing has remained constant: the evolution of the home-based environment has forever changed the way we create and record our music.

The author wishes to thank Ryan Smith, Artist Relations Manager at Shure, for his help in arranging this interview.